Look Ugly and Do as Much as Possible by Eli Bowe

No one looks pretty on a Zoom call. Of all the national awakenings in 2020, perhaps this is the smallest and easiest to digest. I haven’t just come to terms with it, however; recently, I’ve found it to be something worth embracing.

****

In her powerful video essay, “RENT – Look Pretty and Do As Little as Possible”, Lindsay Ellis critiques the solipsistic, bohème philosophy of the famous musical’s (specifically the 2005 film adaptation’s) protagonists. As engaging a 45 minutes as anything I’ve watched, I give it my wholehearted recommendation (although, would-be viewers should be forewarned of strong language in the piece’s conclusion).

Whether by fate or good fortune, I happened to discover this critique just as I began turning my attention toward the end of my two-year stint as an AmeriCorps member. Daily, I find Ellis’s message returning to my mind as I reflect on my time in Montana alongside service members, nonprofit leaders, and struggling citizens. I don’t believe that any piece of media could better encapsulate the lessons I have learned or the gradual sea change propagated in me by my decision to accept an offer from Montana Campus Compact AmeriCorps.

The characters in RENT, this group of young “idealists”, used to be inspiring to me. There was a time when their dedication to Art (with a capital ‘A’) was singularly invigorating, and a perfect encapsulation of my worldview. As far as I was concerned in that period of my life, moral responsibility extended to self-expression, and expressive authenticity was bi-conditionally dependent upon the hopelessness of one’s situation. The mystique of living desperately like the musical’s cast of characters was alluring.

For the longest time, I was completely blind to the irony and tantamount horror of these characters’ attempts to voyeuristically appropriate the experience of New York City’s homeless, or their willingness to sing about upending the status quo while never once dwelling upon their ability to support the anti-AIDs movements and protests of which their contemporary world was redolent. No, I was much more caught up in the flash and pizzazz.

Without a doubt, my motivations in 2018 when I enrolled in AmeriCorps were as lackluster as any of these persons’. I was almost entirely concerned with what national service could do for me, albeit baked into a vague desire to Make the World a Better Place!™ I had no inkling of what form such an attempt might take, and I think that the truth of the matter is few recent college graduates do. But it’s here that we can find the real value of national service. It opens participants’ eyes to truths about their communities and their responsibilities by forcing a reckoning with situations that, thitherto, they may have only ever approached theoretically.

In the past two years, the simplest truth that I’ve learned, in stark contradiction to the philosophy of RENT, is that poverty is not glamourous. It is not très chic to live paycheck to paycheck, persisting in constant exhaustion and worry. The artistic renderings of poverty to which we become accustomed are created with the intention of appealing to tastes and sentiments of those who can afford tickets (which is to say, not those whom the pieces profess to depict), and in that capacity, they are exercises in the mollification of the audience’s shame, which meanwhile titillate with fantastical depictions of life below the poverty line.

From my own experience, I can give assurance that this sort of living is not secretly beautiful. Quite to the contrary, it is “poignant” in the original meaning of the word (an intense, sharp pain). It is not a fantasy when one subsists on rice and beets for two weeks, then collapses in tears of joy after finally affording peanut butter. It is not tragedy. It is not comedy. It is mundane, insane reality.

None of this is to say that service isn’t meaningful and impactful. In fact, it is precisely such eye-opening that allows it to be so powerful. The value of my service came in the form of turning my attention away from desires to convert the experience into something “useful” by transmuting it into so many units of Art. Those naïve sentiments have been subsumed by a wish to turn myself into someone useful who uses skills and knowledge to actively redress struggles in the world; struggles that we are all too often hesitant to admit exist actually and concretely here in the United States.

Substance abuse, mental distress, hunger, fear, poverty— for those who have learned to see them, they are difficult to miss. And at this point in my life, I want to do more than sing protest songs or make grand, theatrical gestures. I don’t want to viva la vie bohème. I want to continue the hardscrabble work of making a difference.

****

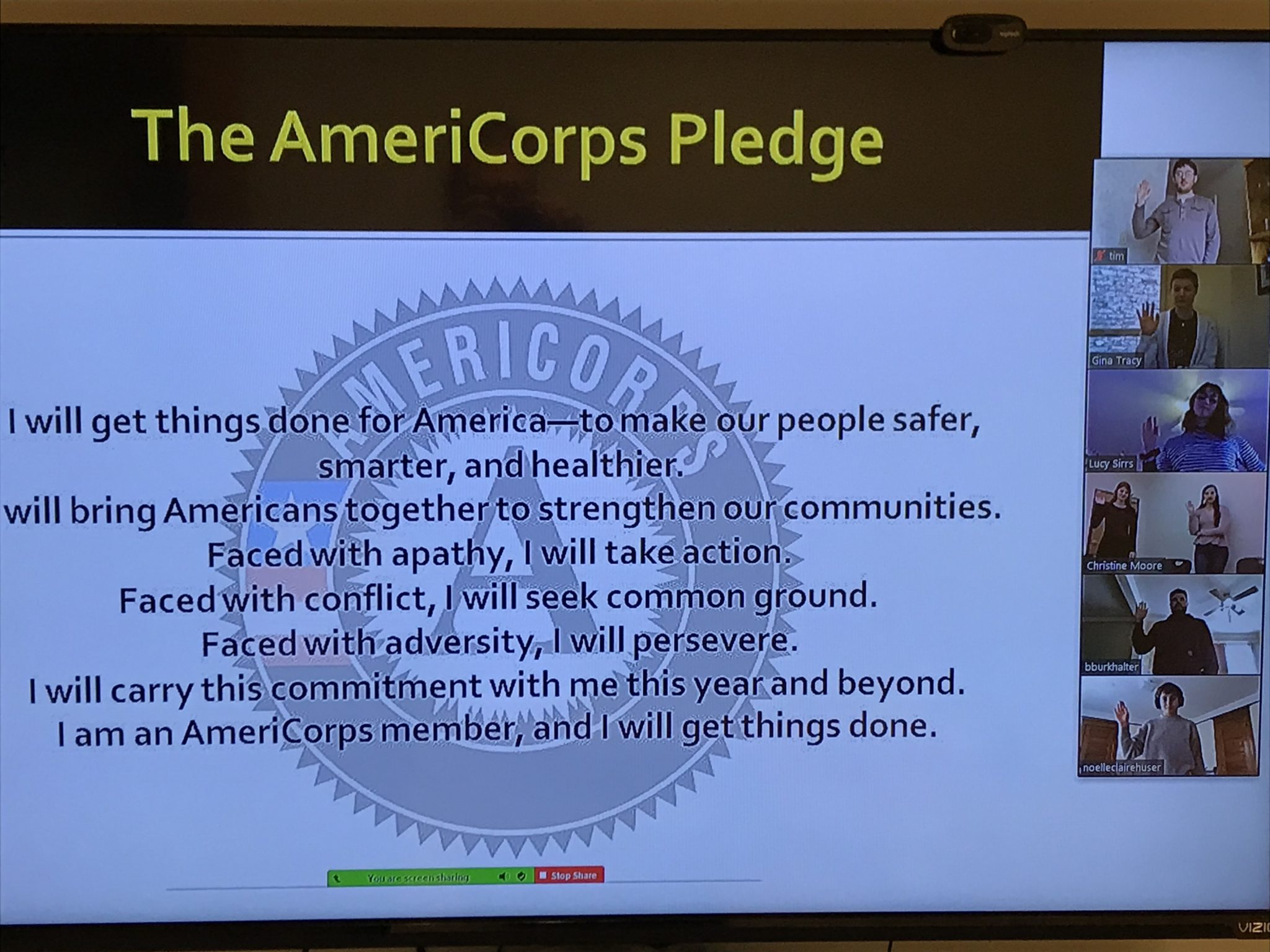

As I meet with AmeriCorps members and non-profit staff in Zoom calls, I’m made to realize, time and again, that none of us look pretty. Washed out faces splashed by unflattering light and subjected to obtuse camera angles may not be inspiring on their own. However, this is a group of people who are dedicated to getting things done— to getting a whole lot done. They are people who pack their days and nights, all their waking hours and their dreams, with helping others in need. They don’t just talk-the-talk. They don’t just wish things would change. They bring their all to making a difference and designing solutions. Sure, they might not be the fanciest or prettiest bunch around, but I couldn’t be more grateful to have spent the past two years of my life serving beside them.

Blog Posts

Blog Posts